Most investors believe they should buy and hold stocks and bonds. They might add modest allocations to alternatives such as foreign stocks, managed futures, gold, or factor tilts. Only a few investors refuse to follow the crowd and go beyond their familiarity biases.

Instead, we try to use “First Principles.” This is the ability to break down complex matters into essential elements and reassemble them in a way that makes the most sense. Socratic questioning and Cartesian doubt can lead to the discovery of first principles.

Aristotle introduced this idea. Creative thinkers like Johannes Gutenberg, Charlie Munger, and Elon Musk have all used it. Here is what Musk said about it:

“People rarely try to think of something based on first principles. They’ll say, ‘We’ll do things because it’s always been done that way.’ Or they’ll not do it because, ‘Well, nobody’s ever done that, so it must not be good.’ But that’s a ridiculous way to think. You have to build up the reasoning from the ground up…”

We developed several principles and adopted one by Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund.

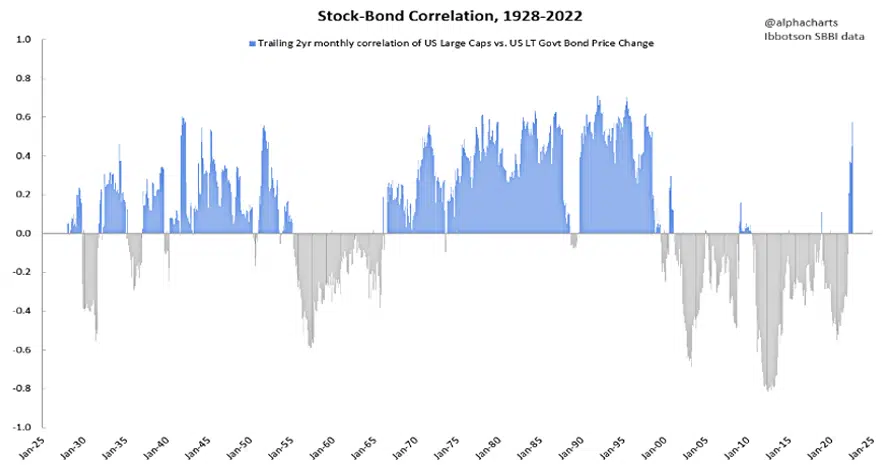

Dalio says the holy grail of investing is diversifying one’s portfolio to reduce risk without impacting return. To do this, you need good return streams with low correlations. Buying and holding stocks and bonds won’t do that. Stocks and bonds do not always have a low correlation.

The long-run return of stocks is nearly twice that of bonds. Extensive use of bonds will lower terminal wealth and drag down long-run portfolio performance.

Trend Following

Here is the most important of our first principles:

Trend following works universally and should be used in all markets. Trend and relative strength are the only factors with over 100 years of research validation.

Trading with the trend is nothing new. The 19th-century economist David Ricardo wrote, “Cut your losses, let your profits run on.” Ricardo became wealthy doing just that.

Charles Dow and his followers used trend following in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In his 1925 book, Richard D. Wyckoff advocated buying the strongest stocks in the strongest industries within the strongest index when trending up during the markup phase of their accumulation-distribution cycle. Wyckoff used his ideas to amass a fortune in the stock market.

In 1935, H.M. Gartley wrote Profits in the Stock Market, which introduced the idea of investing with moving averages. In 1948, Robert D. Edwards and John Magee wrote their classic Technical Analysis of Stock Trends. In the 1950s, Richard Donchian discussed the value of trading commodities using a 5- and 20-day moving average crossover. He later developed his 4-week channel breakout approach, which became well known in the 1970s.

However, trend following has never gained mainstream acceptance. This may be partly because of the academic community’s skepticism after decades of belief in highly efficient markets. “Limits to arbitrage” can keep away institutional investors who fear losing clients during those inevitable times when performance lags.

Most investors relegate trend following to a minor part of their portfolios, if at all. They equate trends with managed futures, whose performance has been sporadic since the 1990s.

Today, trend following, like momentum, can be explained behaviorally as initial inertia and skepticism followed later by trend continuation because of herding. As such, trend following should work best with markets subject to psychological excess, such as the stock market. As we will see, plenty of research supports trend following applied to assets other than managed futures.

Types of Trend Following

I became convinced of the efficacy of trend-based trading in the 1980s when I managed hedge funds employing a combination of trend-oriented traders like Paul Tudor Jones, Louis Bacon, Richard Dennis, Monroe Trout, John W. Henry, and others.

Momentum is a subset of trend following, but other trends also exist. I learned there are three types of trends:

- Rate of change, including variations like moving averages

- Market structure, like chart patterns and Dow Theory

- Breakouts – volatility or channel

Rate of Change

Rate-of-change is the basis for absolute (time series) momentum. It has been effective long-term across many assets, as seen here and here.

In their 2014 book, Greyserman & Kaminsky show that simple rate-of-change outperformed buy-and-hold since the beginnings of the stock market in 1695, the bond market in 1300, and many others. (You can see this by clicking the book’s “Read Sample” button on Amazon.) This approach also reduces the risk of extreme downside exposure.

Moving averages are another indication of rate-of-change. They are likely the most popular form of trend following. As seen here, they have also received more attention from the academic community in recent years.

Market Structure

Market structure includes charting patterns and indicators like the Dow Theory. Lo, Mamayski, & Wang (2000) conducted the first rigorous academic study of chart patterns. Because their research showed chart patterns could have practical value, it took them twice as long as usual to get their paper published in the prestigious Journal of Finance.

Charles Dow was the first co-publisher of the Wall Street Journal and is best known for the Dow Jones averages. Dow and his followers discovered a way to identify the primary trend of the stock market using market structure and agreement between the market averages. Brown, Goetzmann, and Kumar (2008) show that Dow Theory was effective in-sample during the 1920s and out-of-sample since then. Jack Schannep updated Dow Theory in his book, Dow Theory for the 21st Century.

Breakouts

There are two types of breakouts. The first uses volatility spikes as a sign of trend continuation. Bollinger bands are often used this way. They envelope a moving average with volatility-based bands. Breaks above or below those bands create trading signals.

The other form of breakout is from price channels or prior highs and lows. Jack Dreyfus, founder of the Dreyfus Funds, became a billionaire by buying stocks that reached all-time highs. This represents the breakout approach.

Chester Keltner introduced Keltner channels in his 1960 book How to Make Money in Commodities. In the 1970s, Richard Donchian’s breakout channels became popular for commodities trading.

In the 1980s, Richard Dennis taught a channel breakout system to his “Turtle Traders,” some of whom still use it today. Donchian and Keltner channels are now included in nearly all trading software and charting websites.

Brock, Lakonishek, and LeBaron (1991) show the efficacy of channel breakouts and moving averages when applied to 96 years of Dow Jones Index data. Recently. I co-authored a paper entitled “A Century of Profitable Industry Trends” that applies Donchian and Keltner channels to 100 years of 48 industry portfolios. We show the effectiveness and adaptability of a channel breakout approach across diverse market epochs.

Our 100-year study joins the ranks of other long-term trend studies spanning 96 years (Brock, et al.), 100 years (Brown et al.), and more than 300 years (Greyserman & Kaminsky). Trend following is the only investment approach with this much long-term supporting evidence.

Factor investing has attracted considerable attention despite a lack of real-world alpha creation after trading costs and other expenses. (See here and here) Yet most investors have ignored trend following despite centuries of positive evidence supporting it.

Implications

Beginning in the 1980s, I spent over a decade working with the best trend-following traders. I have a lot of confidence in this approach. Our investment models use all three trend following methods and emphasize channel breakouts.

You may not reach our confidence level in trend following, but becoming familiar with trend research may help you accept trend following as desirable for your investment success.

_________________________________________________

Special thanks to George A. Schade, Jr. for his editorial assistance.