I have been looking forward to Jack and Wes’s new book. It is the only book besides my Dual Momentum Investing that relies on academic research to develop systematic momentum strategies. My book uses a macro approach of applying momentum to indices and asset classes. Wes and Jack (W&J) take the more common approach of applying momentum to individual stocks.

W&J begin their book with an excellent question. Since there is ample research showing momentum to be a superior investment approach over the past 200 years, why isn’t everyone using it?

W&J do a good job explaining the behavioral biases that keep many investors away from momentum. W&J also discuss marketplace constraints like advisor career risk when momentum underperforms its benchmark.

In Chapter 1 W&J gives a short history of trend-based and fundamental analysis-based investing. They show that both approaches can work.

In Chapter 2 W&J discuss irrational traders who can dislocate prices from their fundamental values. In the case of value, investors overreact in the short-run to bad news. In the case of momentum, investors underreact to good news.

Investment managers are hired to exploit long-run profit opportunities, but their performance is judged by investors looking at short-term results. Advisors who continue to focus on longer-term opportunities, like value or momentum, may get fired. This is one reason why anomalies like momentum do not get arbitraged away.

In one of the key points of the book, W&J discuss the importance of sustainable investors as well as sustainable alpha. Gregg Fisher once said, “We don’t have people with investment problems. We have investments with people problems.” Investors often lack the requisite patience to stay with their chosen strategies during inevitable periods of benchmark underperformance.

To better prepare investors for challenging times ahead, W&J highlights the risks associated with value and momentum investing. They point to Julian Robertson’s Tiger Funds that lost almost all their clients by sticking to their value model in the late 1990s. Value underperformed the market in 5 out of 6 years, sometimes by double digits. W&J makes this interesting statement, “True value investing is almost impossible.”

What can investors do about this? W&J points out that momentum is largely uncorrelated with value. This means an investment in momentum can make value investing more tolerable. But momentum and value are largely uncorrelated only when their market risk is hedged. Long-only momentum and value are correlated to the market and to each other. All three can simultaneously experience large bear market losses.

In Chapter 3 W&J gives a brief history of momentum and the important psychological challenges facing momentum investors. W&J shows that momentum, like value, can underperform over long periods. They point to a 5-year stretch when momentum underperformed the broad market by 15%. Staying the course during times like that can be a challenge for any investor.

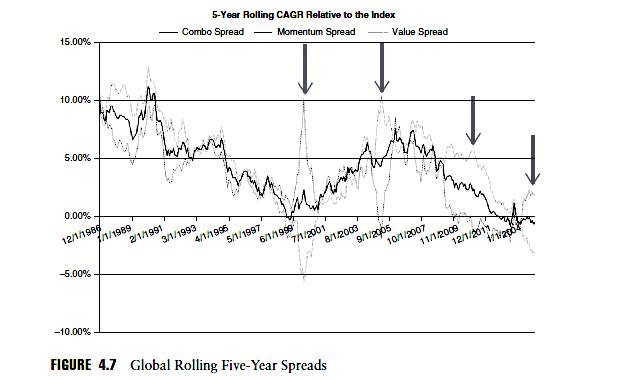

In Chapter 4 W&J demonstrates that a 50/50 allocation to value and momentum can reduce the tracking error of separate value and momentum portfolios during extended periods of relatively poor performance. What may also be worth noting is the decline over time of both value and momentum premia. Both value and momentum may underperform the market simultaneously. Their chart below is consistent with Bhattacharya et al. (2012) and Hwang & Rubesam (2013) who find that stock momentum premia and profits have disappeared since the late 1990s. This underperformance of stock momentum is longer than can be explained by normal tracking error.

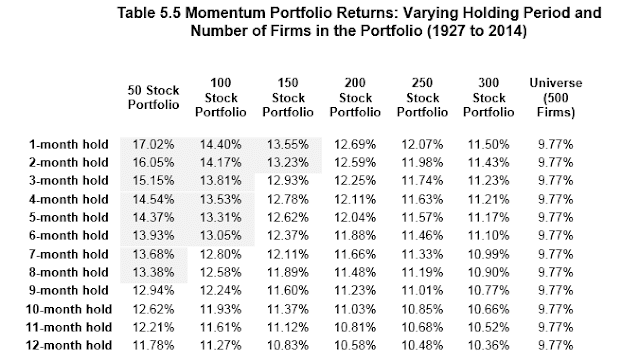

In Chapter 5 W&J shows that frequently rebalanced, concentrated momentum portfolios perform best.

Stock momentum is a high turnover strategy, and many momentum stocks are volatile with wide bid-ask spreads. Therefore, there may be some price impact from trading in momentum stocks. This is especially true for frequently rebalanced, concentrated momentum portfolios.

W&J does say that concentrated portfolio/higher rebalance frequency is not a good approach for large asset managers with billions to invest because of scalability issues. But most investors draw upon the same universe of momentum stocks. Alpha Architect shows the top 100 momentum stocks on their website each month. All investors, not just multi-billion-dollar asset managers, may experience adverse price impact from trading the same momentum stocks as everyone else.

W&J points to a paper in the Journal of Financial Economics by Lesmond, Schill, and Zhou (2002) called “The Illusionary Nature of Momentum Profits.” Lesmond et al. conclude that after transaction costs, momentum profits are largely illusionary. W&J also mentions research by Korajczyk and Sadka (2004) showing that stock momentum has a limited capacity of only about $5 billion.

Offsetting these arguments, W&J presents findings by Frazzini, Israel, and Moskowitz (2014) of AQR. Frazzini et al. argue that trading costs are manageable using optimized trading of proprietary data from 1998 through 2011 if one is willing to accept added tracking error. But the Frazzini et al. study applies to all stocks. It includes a broad mix of momentum stocks that may not be representative of a focused momentum portfolio.

Chapter 6 is where W&J explains path dependency and why it matters. They cite research by Da, Gurun, and Waracha (2014) showing that smooth and steady past performance is preferable to jumpy performance.

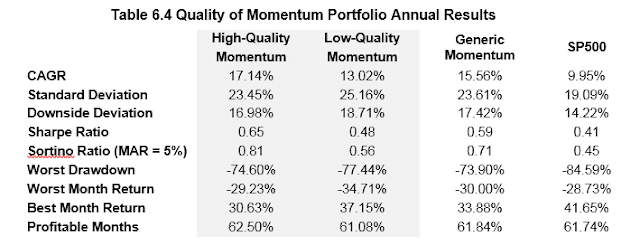

To implement this idea, W&J advocate double sorting stocks on both 12-2 month momentum and the percentage of positive daily returns over the past 252 trading days. What they call “high-quality momentum” are top decile momentum stocks with the largest percentage of positive daily returns. The results below are from 1927 through 2014. Transaction costs are not included.

The improvement in high-quality over generic momentum performance looks good. But a possible warning sign is W&J’s statement at the beginning of Chapter 6: “For over a year, we examined every respectable piece on momentum stock selection strategies we could find…”

Extensive data mining greatly increases the odds that favorable results may be due to chance. Say you have some studies each showing no significance of being correct at the 95% confidence level. If you examine 20 or more of these studies, there is a very good chance one of them will look significant even though the chance of it being correct is still only 5%.

In Chapter 7 W&J attempt to further enhance momentum by adding seasonality. In the turn-of-the-year or January effect, investors engage in year-end tax-loss selling. They hold on to their strongest stocks and may buy more as replacements for the stocks they sell. This can create abnormal profits in these stronger stocks.

Window dressing to make quarter-end portfolios look more attractive may also cause investment professionals to sell losers and buy winners before the end of the quarter. To take advantage of these seasonal tendencies, W&J advocate rebalancing their momentum portfolios at the end of February, May, August, and November instead of each calendar quarter.

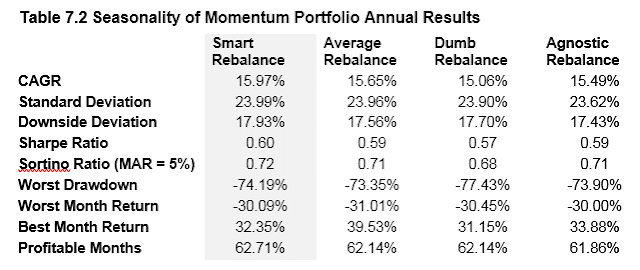

Here are the results from incorporating seasonality as “smart rebalancing.”

There is very little risk-adjusted improvement over agnostic (generic) momentum as you can see from the increase of only .01 in the Sharpe and Sortino ratios. It seems like W&J are using seasonality this way for marketing purposes. But since portfolios are rebalanced quarterly anyway, there should be no harm in picking non-calendar ending quarters to do it.

In Chapter 8 W&J suggests that readers address the trading cost issue by comparing the analysis presented in Lesmond et al. to Frazzini et al. There are other studies that could also be used for comparison purposes, but W&J does not mention them.

W&J then does an in-depth analysis of “quantitative momentum” with respect to reward, risk, and robustness. W&J says, “… strategies like value and momentum presumably will continue to work because they sometimes fail spectacularly relative to passive benchmarks.” This may not be great news for those who at that time hold momentum or value stocks. But W&J offers these words of encouragement, “The ability to stay disciplined to a process is arguably the most important aspect of being a successful investor” (emphasis added).

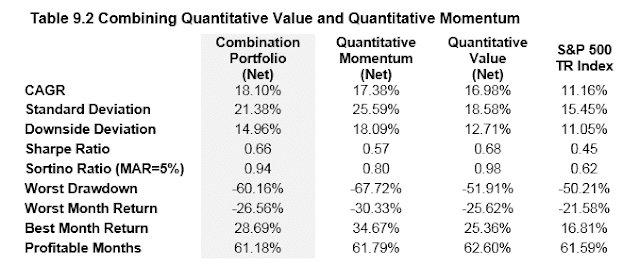

In Chapter 9 W&J looks at a recommended 50/50 allocation to equal weight, quarterly rebalanced momentum and value portfolio from 1974 through 2014.

The combined portfolio return is higher than momentum or value on their own. The combined portfolio has less tracking error vis-a-vis the broad market. Combining value and momentum also shortens both the length and depth of periods of benchmark underperformance.

But volatility and drawdowns are still high. So as a final tweak to their approach, W&J applies a trend following overlay to the combined value and momentum portfolio. If a 12-month moving average of the S&P 500 index is greater than zero, they hold the combined portfolio. If the moving average is less than zero, they hold Treasury bills. Using this trend filter, the worst drawdown of the combined approach goes from -60.2% to -26.2%. But investors give up 1.5% in compound annual return, and there is an increase in tracking error.

My research shows that trend-following is more effective when applied to broad stock indices rather than individual stocks. The reason for this has to do with volatility. The standard deviation of W&J’s quantitative momentum and combined portfolios are 25.6% and 21.4%. The standard deviation of the S&P 500 index is 15.5%. Higher volatility means you give up more profit before you can exit or re-enter stocks when using a trend following filter. This is why combined stock portfolio investors give up 1.5% in annual return, while index momentum investors actually earn higher returns from adding a trend following filter.

W&J finishes up by again mentioning relative performance risk. One cannot stress often enough the warning that myopic investors give up potentially superior results when they become nervous or impatient and abandon their strategies.

In an Appendix, W&J examines some possible enhancements to quantitative momentum. These include earnings momentum, proximity to 52-week highs, stop losses, and absolute strength. Although W&J uses the terms interchangeably, you should not confuse absolute strength with absolute momentum. Otherwise, their analysis here is good.

Overall, I recommend Quantitative Momentum for the following reasons:

1) Its emphasis on the importance of sustainable investors who can keep the big picture in mind and not be swayed by short-term performance

2) Its good review of momentum principles and behavioral biases

3) Its rigorous research in the book’s Appendix